An anecdote

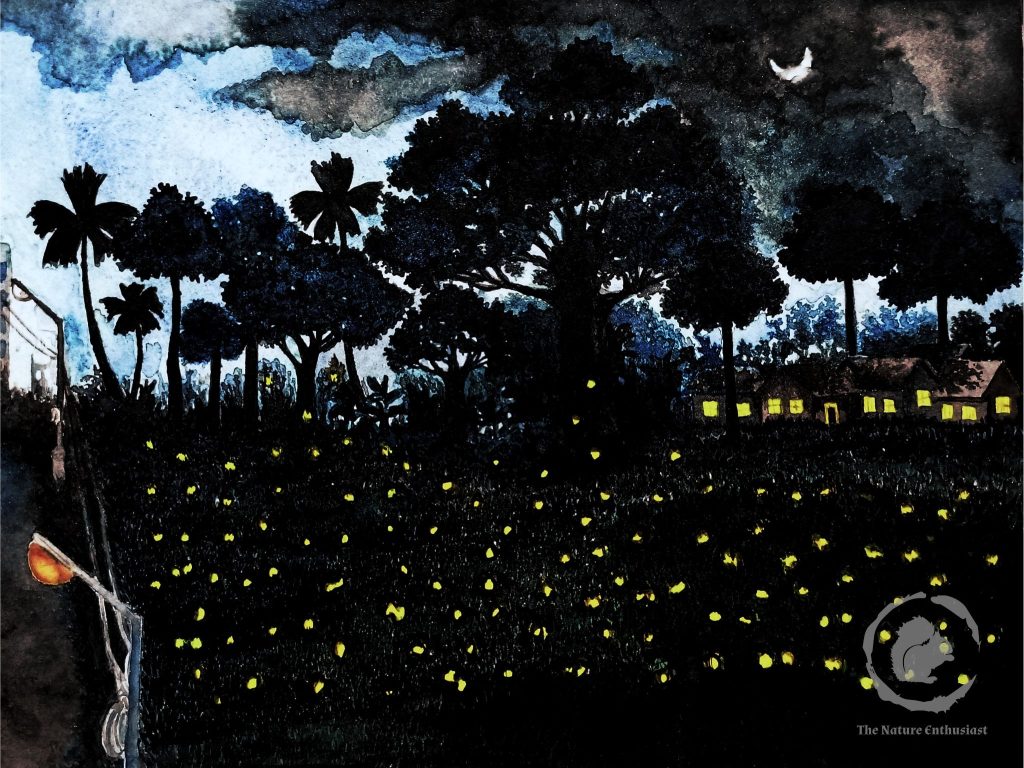

There used to be a place, on the way from the library to my house – a large, neglected field where weeds grew wildly and the grasses were waist high. A large banyan tree stood in the centre of the field towering high over all the other trees that appeared to cower down in front of its magnificent glory. Beyond the little forest was a small locality, a group of five to seven houses, all one storey with roofs of burnt clay tiles. On dark new moon nights, the dull yellow lights from the windows looked like pairs of ghost eyes staring at the pitch-black field. The trees were home to numerous birds and bats while the grass below housed crickets and cicadas that entertained the residents all night long with their rapturous concerts which went on till the break of dawn.

Back on the road that passed this stretch of land stood two tall lamp posts twenty feet apart with their giant swollen glass heads peering down upon the shiny asphalt. One of the lights almost never woke up all night despite several attempts from the locals to cure it of its sleeping illness – the authorities turned a deaf ear to this dark situation. The other lamp was prone to catching cold on moist rainy days, turning red with fever, coughing hoarsely spitting tiny sparks of electricity every other minute. It was however jubilant on dry breezy nights.

One such summer afternoon it had rained. The stretch of road passing the field on my way back home from the library was pitch dark as expected. The dead lamp stood like a ghost while the sick one crackled and flashed red erratically. A barn owl screeched annoyingly from a distance in its shrill monotonous tone. Smoke rose high up into the air from the cluster of houses beyond the giant tree beckoning human presence but there were no ‘ghost eyes’ to be seen that night – a power outage probably. A luminous crescent moon hung against the dark grey night sky, a little higher than the top branches of the great banyan tree while webs of dark scanty clouds crossed it swiftly. The cicadas were having a feisty time. Something fluttered above my head drawing my attention to it – a bat.

It was an ominous night – the one you read about in spooky stories. Once my eyes had adjusted to the darkness I looked closely at the field. I witnessed a sight that I had never seen before – one that I shall remember my whole life. Swarms of fireflies glowed in the darkness. I had seen fireflies in this part of the town before but never in such large numbers. They were prancing around above the shrubs and grasses painting bright blinking dots of yellow-green on some imaginary black canvass. It was hard to fix my eyes to one spot as streaks of greenish yellow lights sped around frantically like tiny comets in every direction possible. As I stood in a daze staring at the glittery celebration a strange thought occurred to me. Maybe I was just imagining things but it seemed so real that it was hard to ignore. I was very much sure the fireflies flashed synchronously – in a pattern almost like some cryptic Morse code – as if they were trying to say something. An eerie feeling made me numb as I stood glued to the spot, not a soul around, gazing into the darkness with its flickering dots of light which hovered like a blanket trying to engulf everything around it in its mystery. A sudden pop from the night lamp overhead brought me back to my senses. The lamp was back. I looked at my watch in the light; half past nine it was. I had already lost fifteen minutes to my nightly adventure. I shrugged my shoulders to shake off the weird feeling and scurried back home.

Amazing fireflies

I discovered much later in my life that what appeared to be some secret Morse code to me was indeed a language of the fireflies – one that only they understood and intrigued scientists for decades. I learnt that the light emitting organs of fireflies were very much like the electric lamps (one of the early human inventions we take pride in) we use today; they have a transparent covering called ‘cuticle’ to allow light to pass through, a shiny reflector behind made of ‘dorsal layer cells’ to direct the light outwards for better visibility, ‘photocytes’ in place of glowing filaments and there are mechanisms that act like switches to regulate the duration of emission of the light pulse.

Another amusing fact among many is that the firefly lantern has an energy efficiency of 98%, much higher than our LED bulbs which has the highest efficiency of 93% for blue light and 42% for green light. It doesn’t just stop at this, organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) which are so popular these days have taken inspiration from our fiery little friends by incorporating the geometry of the firefly lantern into making OLEDs and have enhanced their light production ability by a whopping 61%. A simple tweak in the surface microstructure of the LED which was inspired from firefly lantern could achieve a light extraction efficiency of 90%. Marvels of nature indeed!

Fireflies are not flies but beetles!

Fireflies are not actually flies they are beetles and fall under family Lampyridae of the insect order Coleoptera. If they were flies they would have been under order Diptera. Bet they couldn’t think creative and ended up slapping the generic term ‘fly’ for anything that flies even if they are a bunch of tiny flying fire balls (a grand source of inspiration!).

If you have been lucky enough to clap hold of a firefly as a kid you must have noticed that the light organs are located on the lower side of their belly at the rearmost end. The photocytes, which are the light producing cells, are arranged in close knit groups forming cylinders standing at right angles to the body surface just below a transparent cuticle through which the light is emitted. These photocytes contain small granules which hosts the chemicals necessary to produce light. The cylinders of photocytes also have nerves and trachea – which make up the respiratory system in insects – running through them. Light production depends on oxygen supply to the photocytes which contains the compound Luciferin in its granules; Luciferin on oxidation via a series of chemical reactions involving the enzyme Luciferase produces a cool light which the firefly flashes briefly. In case you are wondering about the names of these chemicals you are probably guessing it right – yes, the name is derived from the Latin word “Lucifer” which means “light bringer”.

Why does the firefly flash?

The flashing is a signal used to find mates. The sole purpose of light production in fireflies is sexual communication. Firefly flashes last about a few hundred milliseconds and the interval between flashes are closely regulated. It is this pattern of flashes which comes handy in species recognition for it is the first step of a successful mating.

The flashing is also used to warn predators of the distasteful nature of some firefly species. Flashes can also be predatory where the prey is lured near only to be captured and eaten. There is also evidence of fireflies using their flashes to light their way while navigating.

Amorous gestures and rapturous concerts

In firefly species of genus Lampyris, the ladies are reluctant to move around (actually they can’t for they are wingless!). They sit in one place and emit a continuous glow signalling the gallant men to come flying to them. The male looks for the brightest female and offers to make love to her. Research has it that brighter the glow is the more fertile is the female. The size of the lantern plays a significant role in perceived brightness and larger females with larger lantern surface area has more eggs and seems to produce a brighter glow which the male definitely could assess.

In Photinus pyralis there appears to be an exchange of code language between the males and females. The ‘love talk’ involves the male flashing for 500ms with 6 seconds between each flash. While still flashing the male also rockets upwards and hovers around for 2 seconds. If the female decides to respond with a flash after 1.5-2.5 seconds of the male flash the male flies towards her flashing again after 3 seconds. Signal given, message received! However, the males can be very strict regarding timeliness and doesn’t respond to female flashes any time after the given time interval. This exchange of light flashes continues until the male unites with the female.

Pteroptyx males form bands to put up an impeccable display of lights. When alone, the males flash regularly with constant time gaps between flashes. When in groups if a male detects a flash within a critical time period of its own flashing it flashes instantly. This gradually leads to the synchronisation of flashes between the males due to their regular flashing behaviour which is inherent. The whole group thus ends up flashing in unison to perform a perfect light show. Pteroptyx ladies are attracted by the flashes of the male group and find their mates from among the performers.

Fireflies and the deathly flashes

But don’t be fooled, for firefly flashes are not always lovey-dovey as we might think it to be – there is vicious manipulation, deceptive identities, honeytraps, crude ulterior motives and murder involved. Female fireflies of the genus Photuris are undoubtedly called the “femmes fatales” of the firefly kingdom. After mating they mimic the flashing pattern of Photinus females. The Photinus males mistaking them for their own females are lured towards them expecting a lovely affair only to end up being eaten by the Photuris females. The meal is not only nutritious enough for Photuris females to fare smoothly through the toll of the egg laying process but also confers her with defence against predators like the Phidippus jumping spider and thrushes. How? Well, the Photinus fireflies contain steroidal pyrones called lucibufagins which the predatory spider and thrushes dislike and so avoid eating them. Photuris fireflies cannot synthesize this compound and are thus left defenceless against predators of the likes of Phidippus jumping spiders. By feasting on Photinus males, the Photuris females acquire this defensive chemical hence achieving protection from predators, resting assured with a longer lifespan. They also protect their offspring for lucibufagins have been shown to lower egg predation as well.

Just another healthy competition

Similar to most cases of sexual selection firefly females are the ones to exercise choice. Just like the evolution of elaborate tail feathers in the peacock depends on the peahen’s preference for longer gorgeous tails according to Fisher’s Runaway Selection Hypothesis firefly females does love the display of all sorts of extravagant feats by the males often pushing them to the limit. By exercising their choice over their mates, females try to choose the healthiest and most desirable male to sire her offsprings who again will go on to win several competitions in future in this game of sexual selection.

Branham and Greenfield showed in an experiment that females of the firefly species Photinus consimilis prefers high rates of male flashes much higher than the rate normally found in the natural population. In natural populations males with higher flash rates are preferred but imagine if this trend continues it can lead to the evolution of even higher flash rates in males – just another case of runaway selection. This preference for high signal rate is however said to be common in females responding to pulsating visual and acoustic signals and is explained to be an evolutionary conserved neural system response to such signals.

A guiding light

The light producing organ of the firefly is called a ‘lantern’ for a reason because it is actually used as a lantern to illuminate a place before approaching it. Photuris species have been observed to emit flashes when landing on a surface or while just simply walking around. This behaviour is believed to serve as an adaptation to avoid blindly running into dangers like spider webs or water puddles.

How the fireflies came to flash?

Light production first emerged in firefly larvae as a warning signal to ward off predators. Later this evolved in adults as a mode of communication and subsequently developed as a sexual signal or ‘love language’. It is common knowledge that pheromones are an important feature of insect communication. However, in some firefly species light communication overtook sexual communication by pheromones so much so that pheromonal sexual communication was put on the backfoot while facing complete obliteration in some species with very well-developed light organs.

Fireflies and us

Fireflies have dominated our imagination for ages as far back in time as the existence of literature. Their nightly aura has found words in poems, folklores, fables and children’s books. The 2009 song “Fireflies” by Owl City have been a popular daily listen for many of us. Many observers and photographers worldwide flock to witness the nightly light display put up by fireflies in regions where they are prevalent like Donsol in the Philippines and Great Smoky Mountains in Tennessee in the United States. Japan is known to host numerous firefly festivals that draws crowds from all across the world. The Indian state of Maharashtra also hosts a fireflies festival every year during May and June when fireflies can be seen in thousands.

But there is a looming threat to these tiny light beings – light pollution and habitat destruction. Fireflies are mostly found near wetlands in the forests and meadows and sadly we have lost more than 35% of the world’s wetlands since 1970 and 488 million hectares of tree cover since 2000. Light pollution is another growing problem not just for fireflies but for every nocturnal insect and even birds. With increased advancement of technologies driving a fast-paced consumeristic life and ever-expanding cities light pollution has increased. Night skies have become 49% brighter in the past quarter of the century.

It is a massive global problem that must be addressed immediately at both the societal and governmental levels but here are a few steps which can be taken solely on an individualistic level. It may be hard to admit but it is almost impossible for an average city dweller to exist without electricity but we can try to minimize the duration and the location where our homes stay lit. It may be just a small step to reduce light pollution but every one of these small steps count to make a significant difference.

For example, try using the interior rooms of the house if possible during the late hours or use blinds to cover the windows to prevent the light from escaping outside.

Switch off unnecessary lights in the garden or on the roof when not required.

Instead of keeping the door light always switched on try using a better communication strategy – if anyone’s at home call them to light the entrance for you only when you come in. When living alone try installing a motion sensor light switch. This way you are not only helping prevent light pollution but also conserving energy which is reducing your carbon footprint.

If you have a small plot of land attached to your house convert it to a small garden. It has been found that patches of green spaces as small as planted backyards in the city can function as a green network providing a habitat corridor for small wildlife.

Keep insecticide and pesticide uses to zero or to the bare minimum levels if at all necessary.

Work with local organisations in conserving firefly habitats and identify areas that need restoration.

While tourism surrounding firefly observation can be a good way to promote global awareness and the revenue generated can be used in habitat conservation, such ecological tourism can also be detrimental to the habitat if not managed properly. So, organizers should pay proper attention to crowd management and also see to it that tourism activities are not causing stress to the habitat.

Concluding thoughts

Now that I reminiscence of the time when I witnessed the enigmatic fireflies that night I feel good that the two streetlamps on my way back from the library were broken for most of the time of the year for I believe it was one of the factors that allowed the fireflies to flourish in that region. Today I live in the same place but a lot has changed and large groups of fireflies are no longer a common sight at night – there still are some fireflies but they have declined in huge numbers.

The loss around us appears to be so huge that attempts at reversing the situation seems futile. But we must not give up hope and work together to protect nature around us. We all can do our small bit and I still believe our unified efforts as a community can reverse the loss to some extent.