Have you ever moved to the city from the country or the other way round? If yes then you must have noticed how the style of speaking and the use of language differ across the two places. It often happens that people who move to the city and settle down there gradually drop their country accents, partly as a natural response of adapting to the new community and partly in a subconscious attempt to fit in. The same phenomenon happens for the country settler too. If we travel a little further and cross borders there are immigrant populations living in a country for couple of generations who have developed novel dialects that sound nothing like the ones found in either of the languages.

There are millions of cases where humans imbibe the language and dialect of a place where they grow up even if they hail from a different ethnic background. Because we have a very well-developed language system and have been using language as the major means of communication for approximately 200,000 years already (according to the Laryngeal Descent Theory (LDT)), the phenomenon continues well into adulthood.

As humans migrated out of Africa and spread across the globe languages diversified. Within each language regional dialects developed – where ‘dialect’ is a form of a language uniquely spoken by a particular group of people belonging to a specific region. Many languages have become extinct so has many dialects which have become outdated and are not spoken anymore. Currently the tally stands at 7164 living languages both spoken and signed globally according to language database site ethnologue.com. Now imagine the number of dialects that could exist across all human languages on this vast planet.

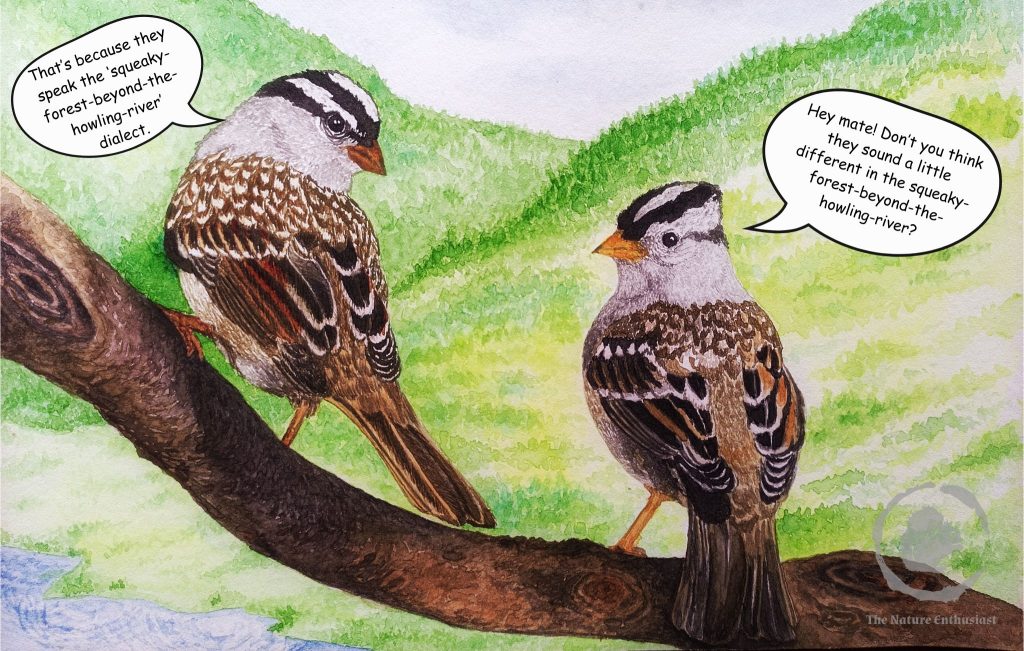

Just when we are about to think of dialects as an innately human undertaking we get stopped midway by a chime of chirpy tiny feathery creatures going by the name ‘bird’. Yes, you heard it right – birds have dialects too!

What are dialects like in birds?

Songbirds of suborder Passeri have very well-developed songs and songs are species-specific such that a species of bird can be identified just from its song.

Parrots and neotropical hummingbirds that show song learning behaviour also have dialects.

Song dialects are variations in certain key areas within the structure of the song in bird populations of a species distributed across a wide geographical area. Birds within a geographical area share commonalities in song structure among themselves – thus having a common dialect – but differ consistently in song pattern with neighbouring populations and hence we can say they have different dialects. For example, in White-crowned sparrows, the song has two distinct portions – the first part is a whistle and the second part is trill – two populations differing in the trill portion of the song can be said to have different dialects.

Do birds have language too?

No, birds don’t have language in a human way of the term but they do communicate with other fellow birds of their own species and sometimes other species with songs and calls.

While some birds like the white-crowned sparrow have each bird sing only one or two song forms (Baptista, 1975) there are birds like the brown thrasher that can sing over 1000 song types (Boughey and Thompson, 1981).

Birds have ‘calls’ which they use for a multitude of purposes like finding food, warning of danger, keeping in touch with group members, roosting and to express agony. But calls differ slightly from ‘songs’. While calls are short sequences of sounds delivered rather randomly, songs are longer, more complex and have a sequence of unique sounds or notes, as in music, that can be pictorially reproduced and has been shown to follow a pattern.

In most birds it is the males who are the singers. But there are species where the females sing too. Male songs propose to serve two purposes – one for establishing and maintaining a territory and two for attracting a mate.

When did we first find out about it?

It was around the middle of the 20th century that scientists discovered that birds have a huge variety of song forms which they use to communicate with members of their own species and also other bird species in a number of ways.

But what’s most astounding of the many facts that emerged from research on the song development in birds was the presence of local dialects.

It was first observed in the White-crowned sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys), a species of American finch inhabiting the Pacific coast. Peter Marler and Miwako Tamura, in a paper published in 1962, described that this bird species had a wide distribution and their songs differed in a way that birds from a certain geographical area sang a particular variant of a song that was clearly distinct from the song of a nearby group. They found this phenomenon very similar to human dialects where the same language is spoken differently by geographically distinct groups of people.

It all started with the White-crowned sparrow

Regional variation in song forms have been observed before but it was only in the White-crowned sparrows that enough data was presented to back the claim. The landmark paper by Marler and Tamura presented the world with sound spectrograms of birdsongs offering a treasure trove of information on how bird songs varied in populations from one region to another. The sound spectrograms were followed by a series of laboratory experiments on song learning in white-crowned sparrows.

Marler and Tamura’s white-crowned sparrows were sedentary by nature, breeding in the same locality they were born in and this helped to develop distinct local song patterns. Young males of white-crowned sparrows picked up songs they heard the adult males around them singing. This was very similar to how humans pick up the local dialect of the place they are born and brought up in. It was this similarity that provoked researchers to describe the little distinctions of song patterns as ‘dialects’.

There is a sensitive period during which a song type could be learned in birds. For white-crowned sparrows trained with recorded songs this critical period lasts till three months from birth. A young bird could be trained to sing any song type typically found in the species within that time frame.

Young males of the white-crowned sparrows listen to the songs of adult males singing in the locality and develop a song of their own later in life based on the memory of what they heard in the early part of their lives. Once the song is embedded in the memory of the young bird during the sensitive period any song experience after that has no influence on the song dialect of the adult bird. Most of the times the song developed is an exact replica of the song they were exposed to in their young age.

In the experiments, young birds were isolated after birth before they had the chance to hear any song and then made to listen to a chosen song during the said time duration. Any time after four months the young bird is not receptive to the stimuli and songs played after that had no effect on the song type that the bird sang later in life.

When isolated just after birth and cut off of all song inputs males developed a very simple song which was somewhat recognizable as a white-crowned sparrow song but stripped of all its ornaments. Konishi (1965) proved that this simple song was inherited as a ‘neural template’ and the bird needs to be able to hear itself to match the sounds it produced to the sounds it had in its head. When deafened the birds produced discontinuous notes that sounded nothing like white-crowned song. The result was still the same after fledglings were trained but deafened before they were able to practise what they had learned during their sensitive period. So, being able to hear oneself is important to materialize any song variant that was learnt and for imbibing local dialects.

How did song dialects evolve?

Vocal learning and site fidelity appears to be two of the preliminary requirements for regional song dialects to develop. As Donald Kroodsma puts it, “… birds that do not learn their songs cannot have dialects, as that term is usually restricted to geographic differences that arise due to learning.”

Whatever is learned must stay at the place of learning if dialects are to appear! If birds disperse after learning a song type no such clustered song distribution pattern is seen and songs are randomly scattered across the population.

It has been observed that subspecies of white-crowned sparrows that are generally sedentary by nature share more songs with their neighbours whereas subspecies from the migratory counterpart share few or no songs with their neighbours.

But before we get to how dialects develop, we need to understand song learning first.

Songbirds learn singing at a very young age by imitating their tutors. But most of the songs they sing as adults develop at a time when they establish their territory or when they enter their breeding period.

These songs are learnt from the most proximate adult males which is a reason why neighbours share the same song types. It often so happens as was observed in a Bewick’s wren by Kroodsma, young birds discard song variants learnt from their father to sing the song type of neighbouring territorial males where he establishes his own territory for breeding.

However, if a regional mapping of the songs sung by the male residents of a large area is done, we will be able to see that a song type varies more and more with distance – the result being patchy groups of males with each group singing a different variant of a song separated by boundaries.

Where there is learning there are bound to be mistakes. Dialects arise from mistakes made during the process of learning. Song development in birds occur by learning from adult males and in many cases this male is the father of the bird.

While learning to imitate the sounds made by the tutor there may occur a mistake. This mistake acts like a mutant – a shift from the normal – and spreads in the population culturally. The learner when he becomes a tutor in the future, teaches this ‘mutant’ song to his disciples that may be his direct offspring or younger males who look up to him for song tutelage. So, each time a song is learnt it is learnt along with the ‘mistake’. There spreads a ‘mutant’ song and more ‘mutations’ or changes are added to the song in each learning scenario. The result is a transformed song that varies markedly from the original song– a dialect thus develops in the region.

Another way how a dialect might develop is by geographical isolation where a physical barrier separates two or more groups of singing males and each group develops their own shared song type which varies from the other group giving the impression of different dialects – songs that are similar enough to be identified as of a specific species but slightly different to pass off as variants.

The purpose of dialects in bird songs?

Songs in birds is an essentially male affair with some exceptions of course. Songs are meant to impress females and woo them in for mating. They are also a way for the singer to announce his presence to his neighbours and hence defend his territory from other males.

Initiation of singing in males is intimately related to the breeding season when the level of testosterone rises in the blood. For the same reason researchers have to inject captive birds with testosterone accompanied by a shift in the light and dark period (mimicking a change of season) to make then sing in the laboratory.

Sharing songs make good neighbours and birds are known to participate in healthy competitions where they match songs with nearby male birds. Birds mimic and pick up song elements during such duels which further enriches their songs.

The complexity of the song determines the sexual attractiveness of the male bird to the female. Complexity in songs is a trait that cannot be achieved overnight. It requires hours of listening, learning, mimicking and practice which can only be achieved with time. So complex songs are seen as a genuine indicator of healthy, experienced and older male birds who have not only shown exceptional survival skills but lived long enough to gather experience in offspring care. These skills are deemed valuable and seen as attractive by young females looking for mates.

But where does dialect fit-in in this scenario?

If songs are learnt from the father and this particular song type stays in the family a song dynasty may come into existence. This song type which we may call a dialect may come as handy in kin recognition for future generations. Even if songs are not passed on from father to son, male birds living in groups can learn a song type or dialect from the dominant adult male in the group. When neighbours share such songs, and they occupy a region a local song dialect develops.

Dialects are among the first stages to a fully evolved novel song that may have implications in species differentiation. A different song in a small breeding population may act as a cultural barrier separating the group from the rest of the population and serve to isolate the mutant song population reproductively.

There is evidence of dialect preferences getting in the way of establishing fruitful reproductive relationships between pairs with each member hailing from two separate bird populations from different localities having different song dialects. Females of white-crowned sparrows have been found to have a higher preference for songs in their natal dialect. Songs from males from her natal region made the female birds restless and perform more copulation solicitation displays.

Reintroduction of birds rescued from traffickers that belong to species that have dialects face another challenge. To make the reintroduction successful authorities have to do a geographical mapping of the dialect so that the rescued bird does not find itself in a habitat where the existing bird population has no resemblance to the dialect it uses. Communication is important for foraging, avoiding predation and finding a mate and dialect is an integral part of this survival game.

Conclusion

With more than half of the human population residing in cities and our ever-increasing demand for energy and resources we are encroaching on habitats that were previously untouched. Our anthropogenic footprints spread so far and wide that it creeps and seeps into cracks and corners of this planet previously thought impregnable, unreachable or unmountable. Our activities negatively impact all life forms in this world in a myriad different ways never thought of before.

As for birds – their populations and diversity are declining at an alarming rate. Many bird dialects are lost with the population either gone or only few individuals left. Often changes in the landscape are forcing birds to change their song structure to better match their new environment for optimal communication.

Species that have somehow managed to survive in the city are facing another challenge – noise pollution. City noises are masking bird sounds making it difficult for them to communicate with one another. Studies have shown that city birds sing at a higher frequency compared to their forest counterparts. The vocal machinery of birds are such that singing at higher frequency also permits the production of sounds at higher amplitude. Singing higher and louder somewhat helps override the constraints imposed by anthropogenic noise in the city. In blackbirds, city songs reach greater distances than forest songs in the noisy city soundscape.

Robin redbreasts in England have shifted the time of their song practice from day to night when the bustling day draws to a close and the surroundings calm down a little. Other species have managed to make some adjustments too to cling on to their city life. But not many can make it in the city.

With habitats fast changing many bird dialects will be lost. Populations singing the same dialect will be split while new ones evolve – although the hope is bleak for with population sizes dropping to critically low levels gradually the traces of their existence shall be completely obliterated and thrown into the dark lanes of oblivion.

Urbanization creates vast expanses of uninhabitable landscapes restricting wildlife to small pockets where they struggle to sustain themselves. Habitat homogenization robs nature or what remains of it of its varied intricacies.

At the end of the day the decision depends on us – the liability falls back on us.

It’s our choice whether we want to buy that exotic looking, cute singing bird shown in a video widely shared across social media for pet or travel by plane when we could easily swap it with a train journey or contemplate about booking a stay at that new luxury resort coming up on the edge of the forest promising a wide angle nature view and a jungle life experience that also claims to be sustainable (but is actually not!).

If we as consumers change the choices we make, even big firms are bound to follow the new trajectory we set for them. So next time we make a decision let’s choose for change. That way we do not have to travel to some distant place to experience nature – nature will find us. Wouldn’t life be dreamlike to wake up to birds chirping in our little gardens? Let us all strive to create a world where we can coexist harmoniously with nature.